Sculpture

Lars Widenfalk

Lars Widenfalk

By Jan Åke Pettersson

In a Scandinavian context, Lars Widenfalk has since many years appeared as one of the principal exponents for a revitalizing of figurative stone sculpture.

Sculpture: Venus EUROPA

Being born in 1954, he belongs to a generation that saw the body be eliminated in three-dimensional art, and stone give way to steel, plastic, and concrete. Against such a background, he has borne his own sculpture back to a new point of departure.

The stone - this element which, through the perspective of natural history, endures eternally - is once again present as an indicator of time, against historic/concrete rooms. Furthermore, through the human body; the only "universal form" where nature and history are seen united. But when Widenfalk opens and peels his stone, it is also to reveal something unexpected in the expected form.

In such a way we are made aware of the fact that art cannot exist without a conscious human act or will. At the same time, the work of art in its entirety does not solely reflect the artist's desire. With a so utterly resistant material, he also lets the stone have its will by that its function becomes to create an antithesis to his own thesis of the work - which, by the end of the working process, appears as a synthesis of man and material - the work of art!

Thus, in Widenfalk's reintroduction to the traditions of figurative stone sculpture, one can trace a reaction against the last two decades' "experimental" fascination for materials, where one has attempted to compensate the often obtrusive absence of a visual meaning in abstract and minimalistic sculpture. By pushing those spectra of natural or technologically created materials to the most fantastic metaphysical significances, often exposed by means of pompously arranged installations.

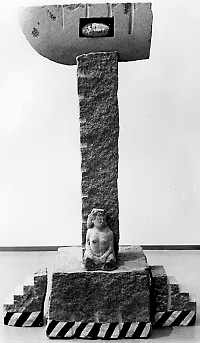

Sculpture: Circle of the Shield

Widenfalk seems to consciously take distance from these often vague complexes of this art by the use of the human body and a far simpler expressed symbolism. Contrary to the classical/romantic method he uses in creating his works, his reaction toward late modernism doesn't draw on a retrogression to any antique ideals of the great traditions, as is noticeable in post modern classicism - still, perhaps one may add, in spite of the fact that many of his sculptures have taken shape in the richly traditional marble workshops of Pietrasanta, northern Italy.

Widenfalk seems to consciously take distance from these often vague complexes of this art by the use of the human body and a far simpler expressed symbolism. Contrary to the classical/romantic method he uses in creating his works, his reaction toward late modernism doesn't draw on a retrogression to any antique ideals of the great traditions, as is noticeable in post modern classicism - still, perhaps one may add, in spite of the fact that many of his sculptures have taken shape in the richly traditional marble workshops of Pietrasanta, northern Italy.

The self-assured, confident type ideal of classicism is something remote to Widenfalk's unobtrusive and intimate figures. But his silent characters still appear robust. Even those that are smaller in size, not only because he often leaves central parts of his pieces as raw cuts, or on account that the material in itself gives them an aura of heavy, physical presence. It is rather his insistence upon the simple, almost naïve form in both figures and objects which creates this special effect of gathered, compact mass. One could say that Widenfalk proximates the robustness in his simplified forms through the truly ethnic of this part of the world - the old Norse folk art. On the other hand, he may arrive at this robust quality by means of the form, which seems inspired by the pre-classicist or archaic sculpture.

The self-assured, confident type ideal of classicism is something remote to Widenfalk's unobtrusive and intimate figures. But his silent characters still appear robust. Even those that are smaller in size, not only because he often leaves central parts of his pieces as raw cuts, or on account that the material in itself gives them an aura of heavy, physical presence. It is rather his insistence upon the simple, almost naïve form in both figures and objects which creates this special effect of gathered, compact mass. One could say that Widenfalk proximates the robustness in his simplified forms through the truly ethnic of this part of the world - the old Norse folk art. On the other hand, he may arrive at this robust quality by means of the form, which seems inspired by the pre-classicist or archaic sculpture.

The latter quality could very well place him and an Italian colleague, Mimmo Palladino, in the same group. But aside from a few thematic parallels, Widenfalk's position in what one could call the archaized art of our time, seems to be different. His formal links rather bring to mind a Swedish, and more expressive sculpting tradition, which Bror Hjort initiated in the 1920s. His anti-cultural vitalism built to a great extent upon borrowed elements of the "primitive" folk art and its coarsely chiselled figuration and ornamentation, while an artist such as Bror Marklund a decade later added an Egyptian, far more supple shape to his art.

Sculpture: The House of the Hunter

Sculpture: A Feather of Time, a Room

of Goodness. Homage to Rolf Björlind While growing up, Widenfalk came to spend every summer in southern Härjedalen, where he encountered not only folk art but also the stone. The part of this county known as the Älvros-belt is where much of the Widenfalk family has its roots. His brother, a schooled geologist, helped him gain full awareness and knowledge about the stone. After years of wood-carving practice, the stone became his principal medium for expression, and the material, which initiated his artistic direction by the end of the 70s.

While growing up, Widenfalk came to spend every summer in southern Härjedalen, where he encountered not only folk art but also the stone. The part of this county known as the Älvros-belt is where much of the Widenfalk family has its roots. His brother, a schooled geologist, helped him gain full awareness and knowledge about the stone. After years of wood-carving practice, the stone became his principal medium for expression, and the material, which initiated his artistic direction by the end of the 70s.

Even at this time, Widenfalk was keenly interested and engaged in religious ceremonies. Having a father who is a minister in the free-catholic church, he was to assist as an altar  boy during his childhood. Later, he became interested in a number of ceremonially inclined religious communions, there within everything from free masonry ordination to rites derived from Egyptian mythology, and theosophy. Common throughout these groups is, among other things, the use of symbolically charged objects, as means for the different ceremonial rites, and important as guides towards spiritual awareness. And it is this object related, ritual factor, which Widenfalk has brought into art, though so profoundly generalized that one can merely sense the mental processes, evoked by the fragmented archetypes' subtle suggestions.

boy during his childhood. Later, he became interested in a number of ceremonially inclined religious communions, there within everything from free masonry ordination to rites derived from Egyptian mythology, and theosophy. Common throughout these groups is, among other things, the use of symbolically charged objects, as means for the different ceremonial rites, and important as guides towards spiritual awareness. And it is this object related, ritual factor, which Widenfalk has brought into art, though so profoundly generalized that one can merely sense the mental processes, evoked by the fragmented archetypes' subtle suggestions.

The central positions given to the fragment in Widenfalk's works may be connected to his archeology studies at the University in his home town, Uppsala. Archeology moves through object related epoches - each other remote, at least in time - where scattered findings of man-made objects and tracks form the basis for systematic guesses about ancestral behaviour - physical and mental life. In this activity, ready answers are seldom given. The same applies to any confrontation with the fragments in Widenfalk's art. He uses these in some way as hints the yet unknown in the expected known. The fragment is there to express something of the eternally imperfect knowledge of ourselves. Through fractures of bodies and objects, he builds a world which doesn't only present itself to us as observers for insight and penetration, but also mirrors the lack of absolute and exact meaning in the real world.

The central positions given to the fragment in Widenfalk's works may be connected to his archeology studies at the University in his home town, Uppsala. Archeology moves through object related epoches - each other remote, at least in time - where scattered findings of man-made objects and tracks form the basis for systematic guesses about ancestral behaviour - physical and mental life. In this activity, ready answers are seldom given. The same applies to any confrontation with the fragments in Widenfalk's art. He uses these in some way as hints the yet unknown in the expected known. The fragment is there to express something of the eternally imperfect knowledge of ourselves. Through fractures of bodies and objects, he builds a world which doesn't only present itself to us as observers for insight and penetration, but also mirrors the lack of absolute and exact meaning in the real world.

Skculpture: House of the Woman with the Lions Head

Assisted by Queen Silvia, King Carl XVI Gustaf plants a Tree of Life in Widenfalk's garden.

1996.

Sculpture: The Pearl-Fisher's Dream

In a series of stone cabinets he has shown the fruit of his soul's archeology by placing a number of embryonic human heads on the fragile shelves of memory. These effeminated, introverted and in Brancusian spirit briefly chiselled head shapes, appear in various works of Widenfalk. Most prominently so when they are found lying in the tower-like chairs which crown his many elevated landscapes. In these monolithic sculptures there are clear references to the customs and architecture of Mesopotamian and Egyptian cultures. But the throne chairs at the top of Temple Ziggurate don't seem to have been used to lead one's thoughts to the religious practices of the old gods.

In a series of stone cabinets he has shown the fruit of his soul's archeology by placing a number of embryonic human heads on the fragile shelves of memory. These effeminated, introverted and in Brancusian spirit briefly chiselled head shapes, appear in various works of Widenfalk. Most prominently so when they are found lying in the tower-like chairs which crown his many elevated landscapes. In these monolithic sculptures there are clear references to the customs and architecture of Mesopotamian and Egyptian cultures. But the throne chairs at the top of Temple Ziggurate don't seem to have been used to lead one's thoughts to the religious practices of the old gods. It is rather in order to bring the observer's attention to a mythological world universally applicable, which orbits the mysteries of life, that Widenfalk's dreaming figures are placed in such charged ritual surroundings. And even this - broken and unfinished sides included- more processually expressed symbolism of life is a typical element in his depiction of humanity. In the granite sculpture "The Pearl-Fisher's Dream" he lets a horizontal boat shape break. The movement which strives sky-wards to underline the expression of mental movement in the closed, archaic face. The title alludes to an atmospheric world which he himself has experienced through taking inspiration from a poem which his father wrote and often recited to him during his childhood.

It is rather in order to bring the observer's attention to a mythological world universally applicable, which orbits the mysteries of life, that Widenfalk's dreaming figures are placed in such charged ritual surroundings. And even this - broken and unfinished sides included- more processually expressed symbolism of life is a typical element in his depiction of humanity. In the granite sculpture "The Pearl-Fisher's Dream" he lets a horizontal boat shape break. The movement which strives sky-wards to underline the expression of mental movement in the closed, archaic face. The title alludes to an atmospheric world which he himself has experienced through taking inspiration from a poem which his father wrote and often recited to him during his childhood.

That sort of poetic searching and low-key, elegiac mood also rests over the sculpture "Woman With Lion Head", whose elongated, whole figure sits in its chair and gazes out towards a distant land. Her severed and scantily fastened arms, rendered her incapable of attaining what she aspires in her realm of experience. The connection between body and hands is broken, and thereby even the connection between thought and action; between dream and reality. But her paralysis and the physical lack of power in the string-tied limbs, merely reinforces the presence of those mental processes that one perceives in her face. And most clearly, Widenfalk has portrayed the infinities of the inner world in the large marble work, "The Longing Woman From Genoa". Like surrounded by the harmlessness of beauty, she sits as though mummified on her throne, without arms or legs. The amputated body is like a tightly packed, softly rounded clod of pulsating organic material. Her yearning eyes will never reach their final goal. With a longing as petrified and immortalized as the inner ocean of emptiness, from which all of our searching originates - the void - which from the moment it arises can never be filled, as Jean Paul Sartre has described the irrevocable existence of missing.

That sort of poetic searching and low-key, elegiac mood also rests over the sculpture "Woman With Lion Head", whose elongated, whole figure sits in its chair and gazes out towards a distant land. Her severed and scantily fastened arms, rendered her incapable of attaining what she aspires in her realm of experience. The connection between body and hands is broken, and thereby even the connection between thought and action; between dream and reality. But her paralysis and the physical lack of power in the string-tied limbs, merely reinforces the presence of those mental processes that one perceives in her face. And most clearly, Widenfalk has portrayed the infinities of the inner world in the large marble work, "The Longing Woman From Genoa". Like surrounded by the harmlessness of beauty, she sits as though mummified on her throne, without arms or legs. The amputated body is like a tightly packed, softly rounded clod of pulsating organic material. Her yearning eyes will never reach their final goal. With a longing as petrified and immortalized as the inner ocean of emptiness, from which all of our searching originates - the void - which from the moment it arises can never be filled, as Jean Paul Sartre has described the irrevocable existence of missing.

Sculpture: Woman With Lion Head

The dream of the hidden pearl in the unknown land becomes merely yet another fragment, which is laid upon the Tower of Babel we built within ourselves, and where the throne-room always remains empty. Thus we are told by the searching sincerity in Widenfalk's lonesomely gazing figures, that it is in a frozen uncertainty one can find the deepest significance - in his plastic Universe; for it is with insight as with stone - if one carves too deep, it is ruined.

The dream of the hidden pearl in the unknown land becomes merely yet another fragment, which is laid upon the Tower of Babel we built within ourselves, and where the throne-room always remains empty. Thus we are told by the searching sincerity in Widenfalk's lonesomely gazing figures, that it is in a frozen uncertainty one can find the deepest significance - in his plastic Universe; for it is with insight as with stone - if one carves too deep, it is ruined.

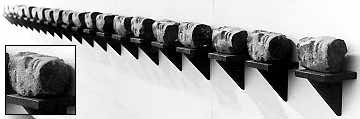

Sculpture: 21 Dreams in a Vanishing Landscape